This year, English Heritage began a partnership with The Courtauld Institute of Art, to work on a collaborative 12 week conservation project on the paintings of Longthorpe Tower.

For several weeks, the principal chamber was filled with scaffolding, and the upper chamber contained heaps and piles of work materials, together with busy Masters students from the Courtauld Institute, working on the paintings.

This has resulted in a full three page article in the English Heritage members’ magazine, and a larger number of visitors than normal have been arriving to see what it is all about.

As my most recent posts have been about other historic places, (visited during the winter closed season), it feels like it is time to re-introduce the Tower for the benefit of new visitors, who may have chanced upon this website seeking more information.

Founders

The Tower was built by the Thorpe family, a local family not of noble origin at all. In fact, they had made their way out of the peasantry (an almost unheard of feat in the hierarchical society of Medieval England). An earlier post of mine below compares their achievement with that of the Paston family from Norfolk, who are much better known, (as a result of the amazing archive of letters they left behind). The Thorpes, like the Pastons, were named after the village they hailed from, because they were not gentry, and did not have a long pedigree going back to the Norman knights who came over with William the Conqueror. Again, like the Pastons, the Thorpes studied hard, became lawyers, made money, and eventually rose to high positions in society.

There are two villages, very close to each other, Thorpe and Longthorpe, and both were owned by Peterborough Abbey. There was a manor house in each, and manor lands owned by the Abbey needed to be managed and farmed so that the Abbey could use the revenues to maintain its prestigious position as one of the wealthiest Abbeys in the kingdom.

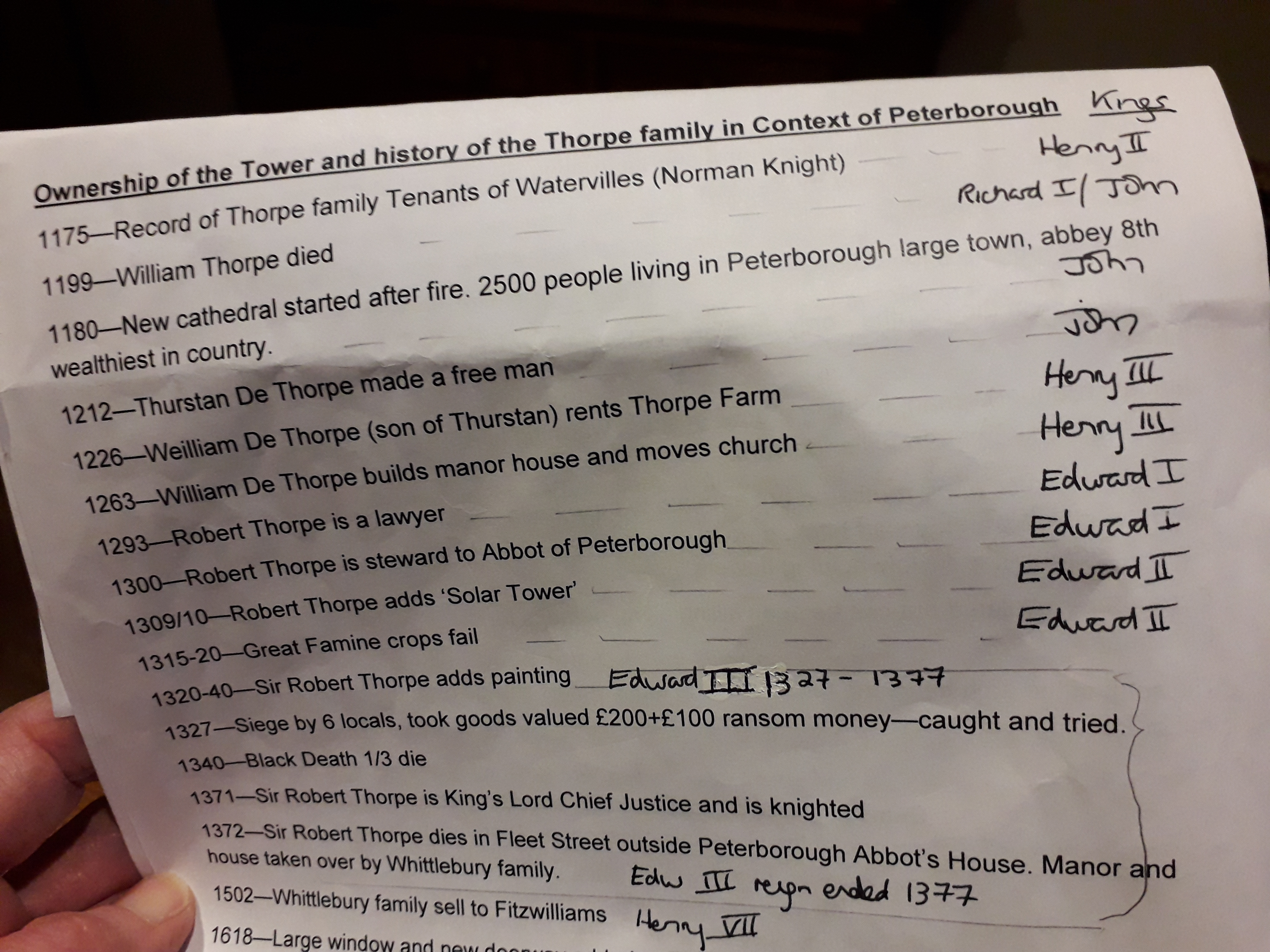

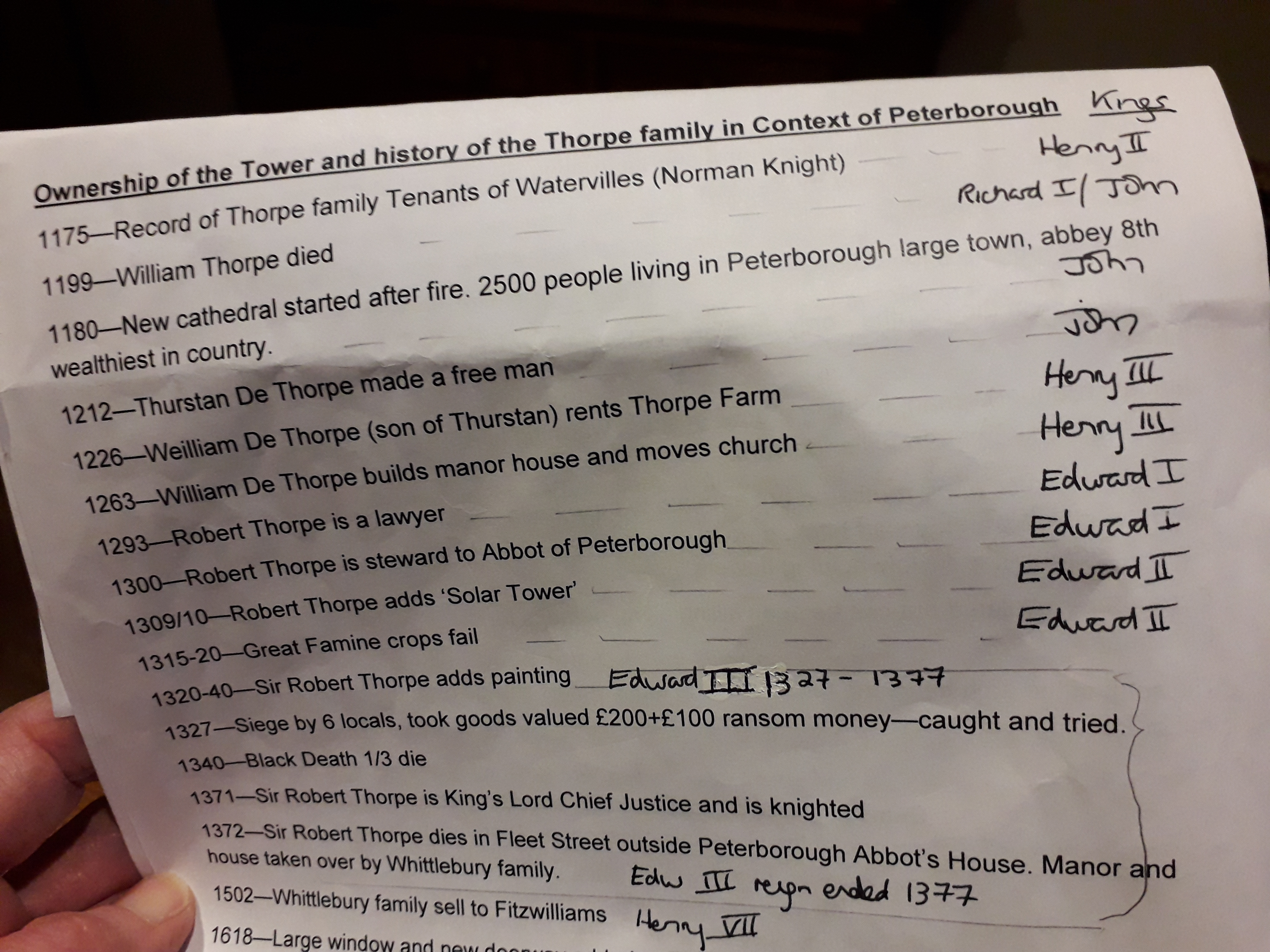

Robert Thorpe the elder, who added the Tower to the Manor House at Longthorpe, was the chief lay steward to the Abbey, an important and well-paid position. Today it would perhaps be called Facilities Manager, or Managing Director of Estates. His legal training would have been very important, and financial management was also a vital part of his role. He collected rents for the Abbey, and later on, his descendant would become Chancellor of the Exchequer. A Timeline for the Thorpe family can be seen below.

The dating of the Tower is around 1309/10, during the reign of Edward II.

Architecture

Adding a Tower to the Manor House was a statement of wealth and prestige. It is thought that Robert Thorpe was likely to have used offcuts of stone from the Abbey buildings, and possibly also workmen from the Abbey to build the Tower, which, to this day, stands out as a particularly tall building.

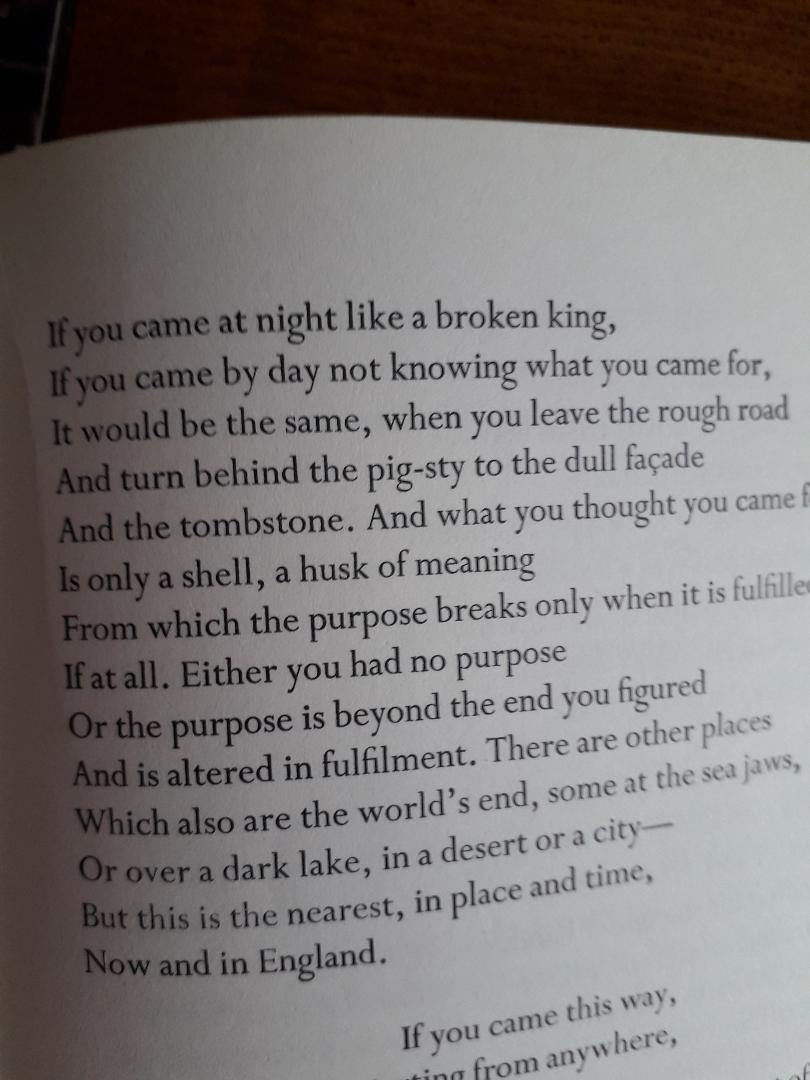

This was not a castle, and although there there is a battlemented area at the top, it was never defended during any war, or civil war, of which there were many during the periods of unrest in the Middle Ages.

It was a sign of status.

There is a striking similarity between Longthorpe Tower and the ducal tower of Siedlęcin, Lower Silesia, in Poland. Both were attached to a Manor House, and would have had a moat surrounding. The architecture of the windows is particularly notable in its similarity:

Longthorpe, window on upper floor.

The Ducal Tower of Siedlęcin. As this was built by a member of the higher nobility, it is on a much grander scale than Longthorpe, but the similarity of design is evident.

Most noteworthy and most important in both the Ducal Tower and Longthorpe are the Wall Paintings.

The Wall Paintings

As in the case of the Ducal Tower, the paintings are of stunning scale and of international importance. Both were whitewashed over for centuries, and survived miraculously. My colleague will write about the paintings in the Ducal Tower, and I will concentrate on Longthorpe.

As this was part of a private family home, the paintings show considerable variety. The themes are both religious and secular, but after the English Reformation it was considered heretical to show any religious imagery at all, so the whole interior would have been whitewashed to avoid any trouble.

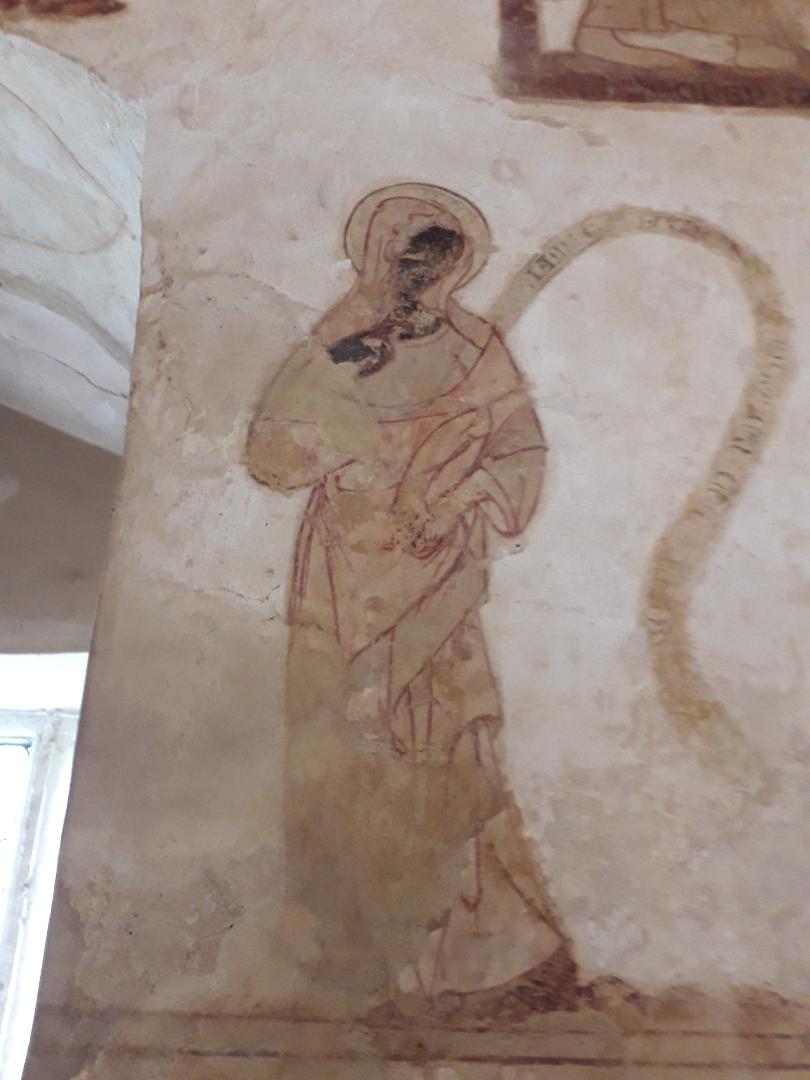

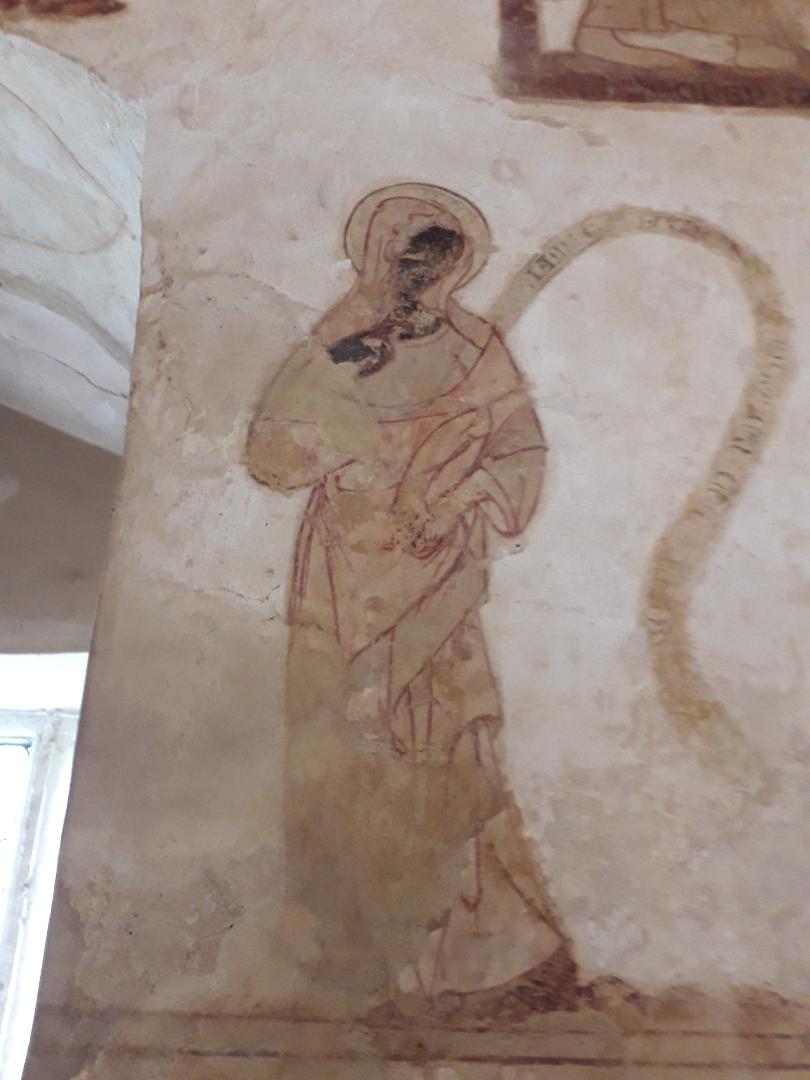

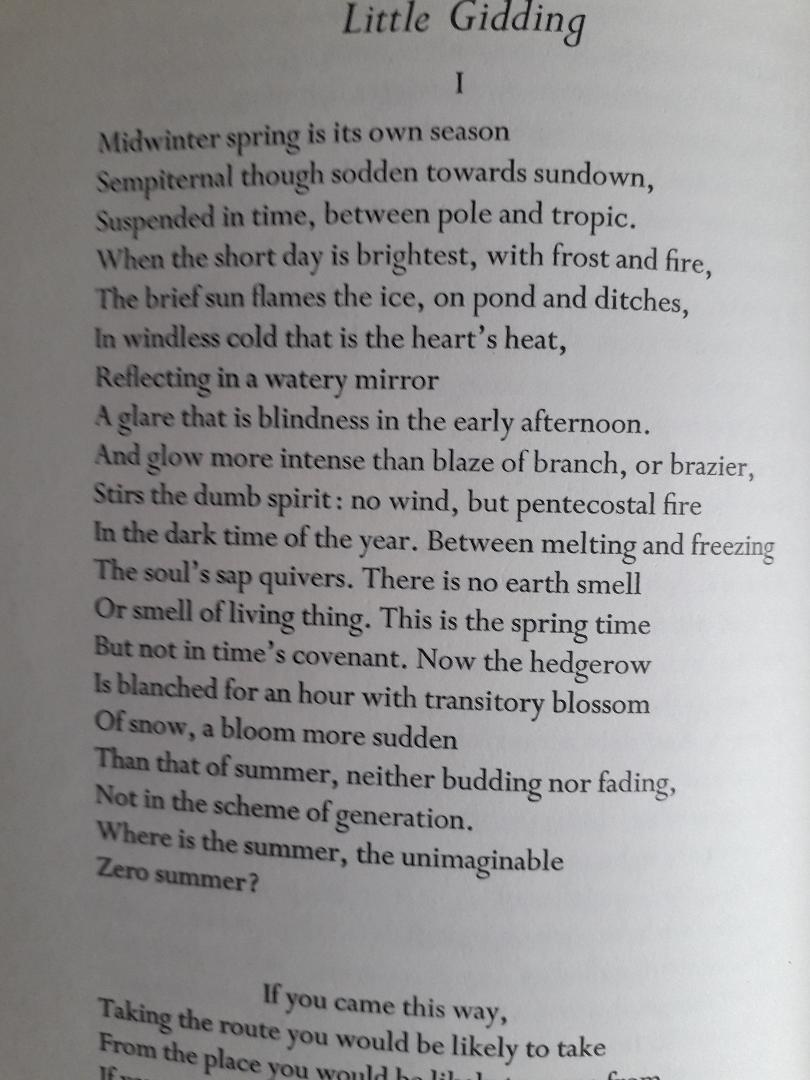

There is a nativity scene, and a depiction of the twelve apostles, each holding a scroll with a sentence from the Apostles’ Creed. Here is a part of the scroll with the words “Spiritus Sanctus” (the Holy Spirit) just visible.

The beautifully even Latin script suggests that possibly monks from the Abbey Scriptorium were drafted in for the work.

One of the “Apostles” turns out to be a woman. This figure represents Holy Mother Church, as the words on her scroll inform us.

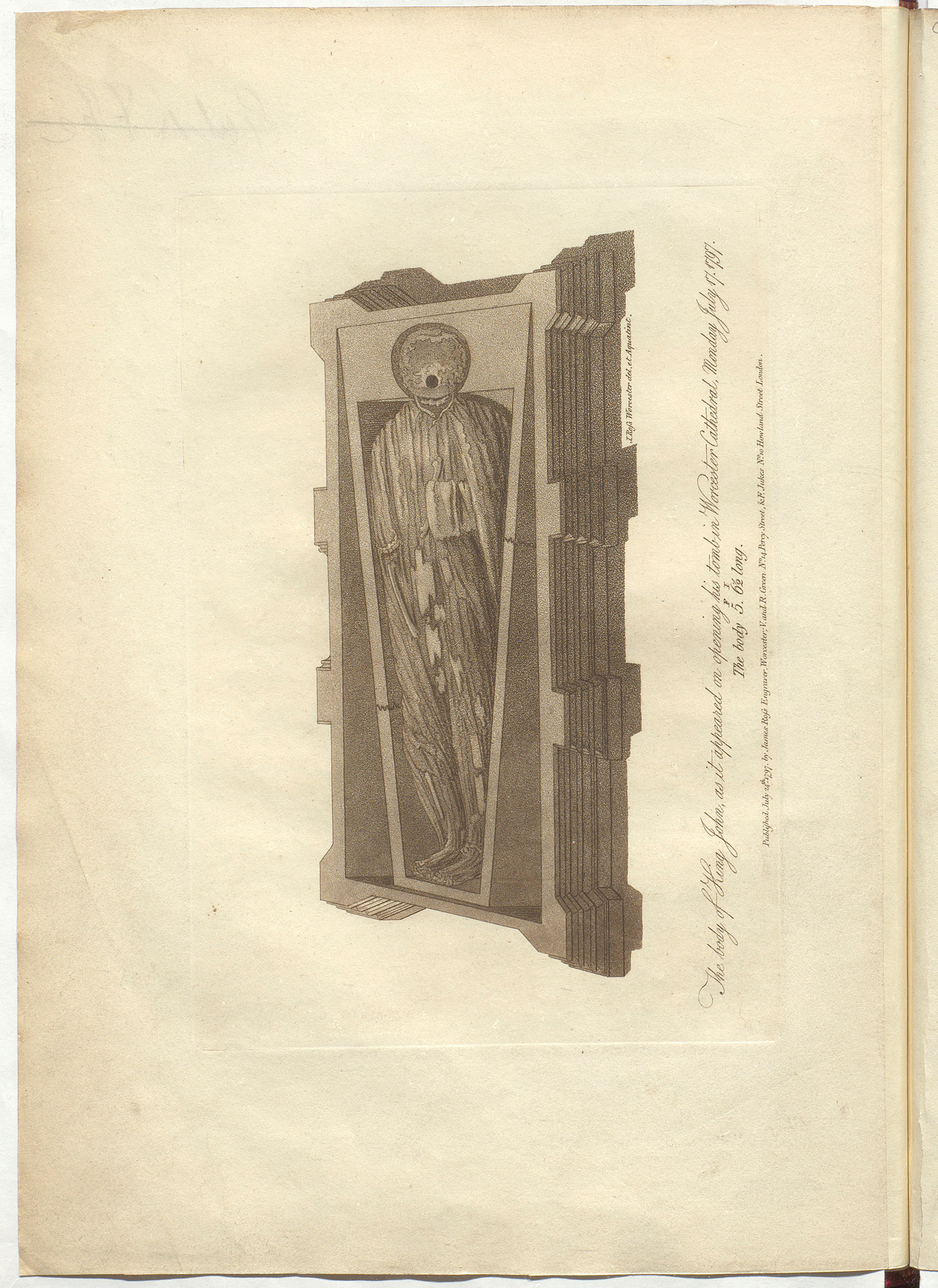

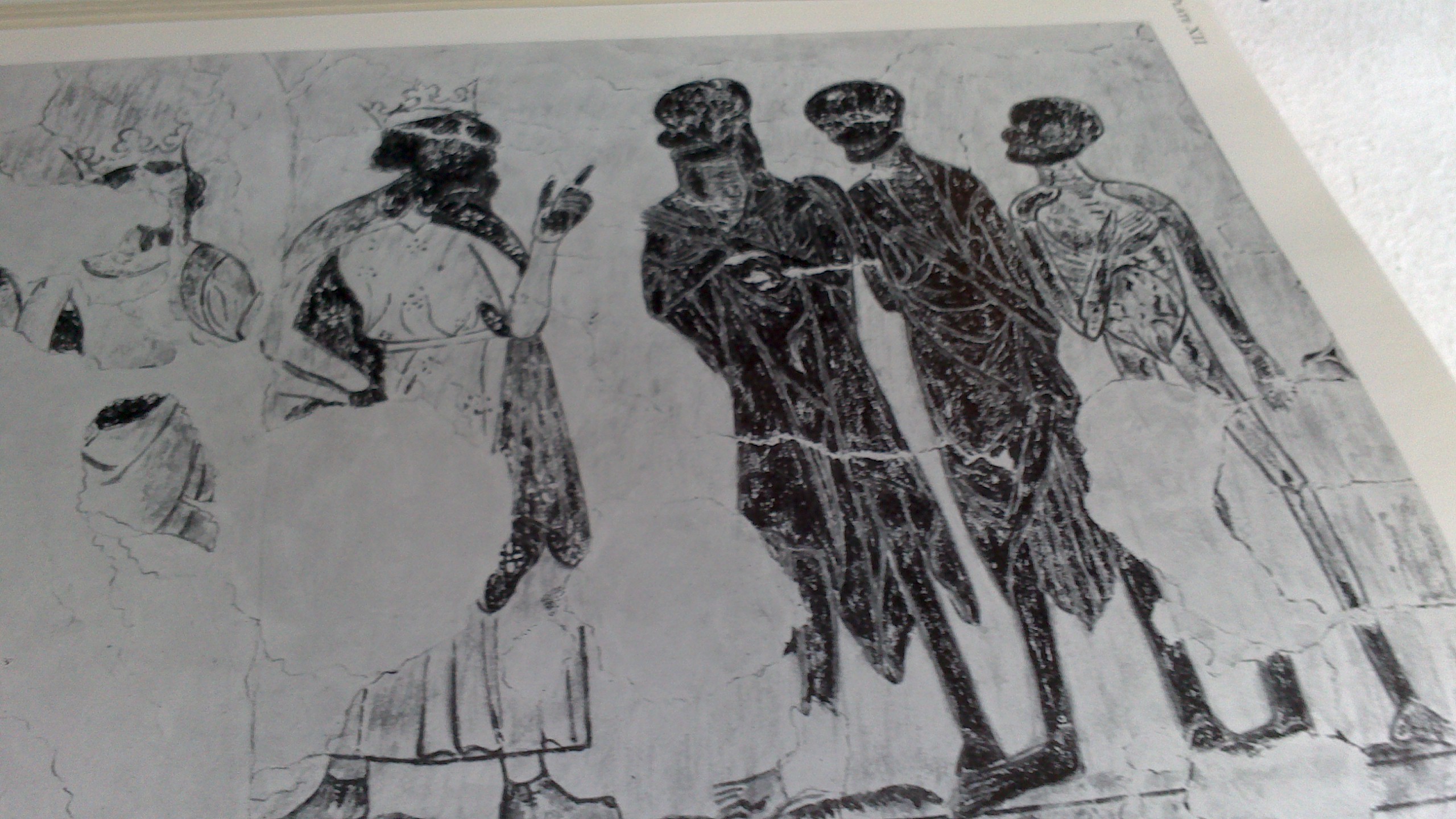

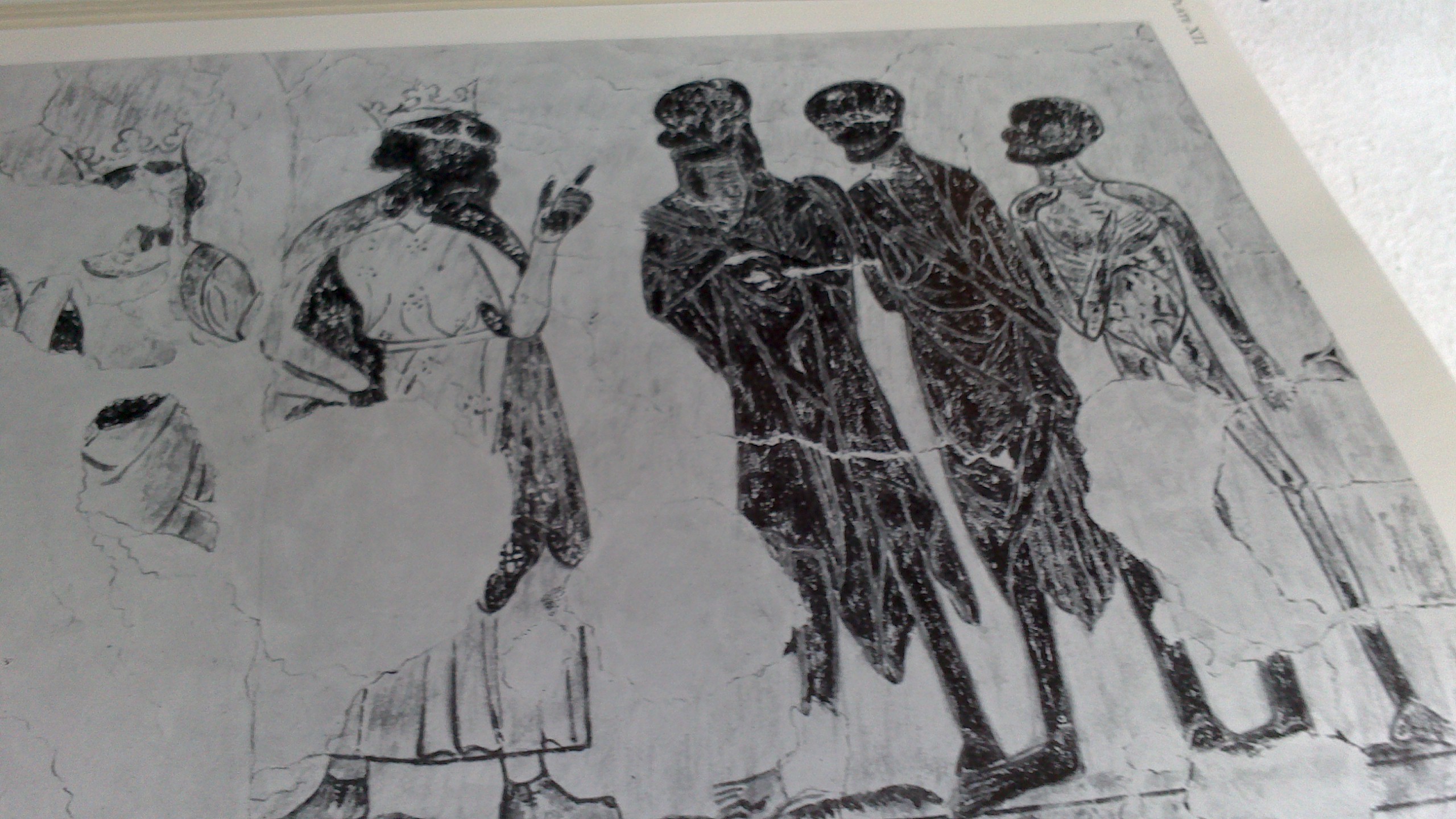

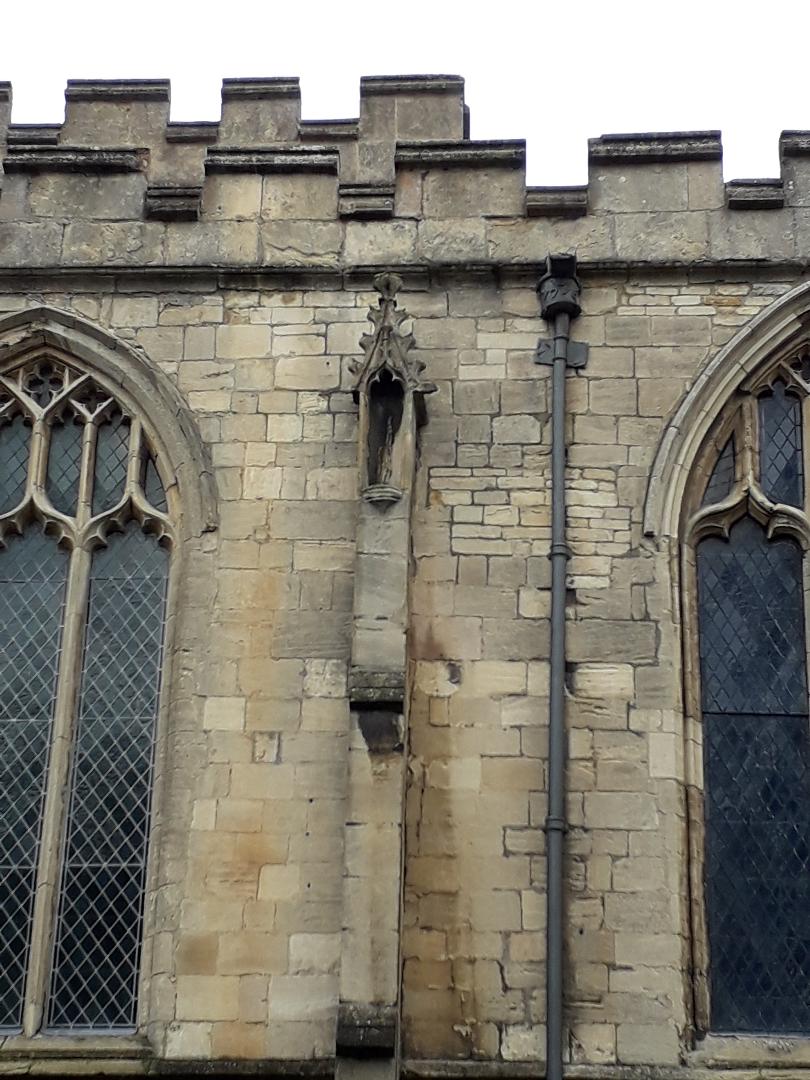

Other paintings, while not religious, have a strong moral tone. An examples is “The Three Living and the Three Dead”.

On the left, three Kings are out in their finery, enjoying a hunt. They meet three skeletons in progressive states of decomposition, the one on the far right being eaten by worms.

The Kings ask: “What is the meaning of this?”

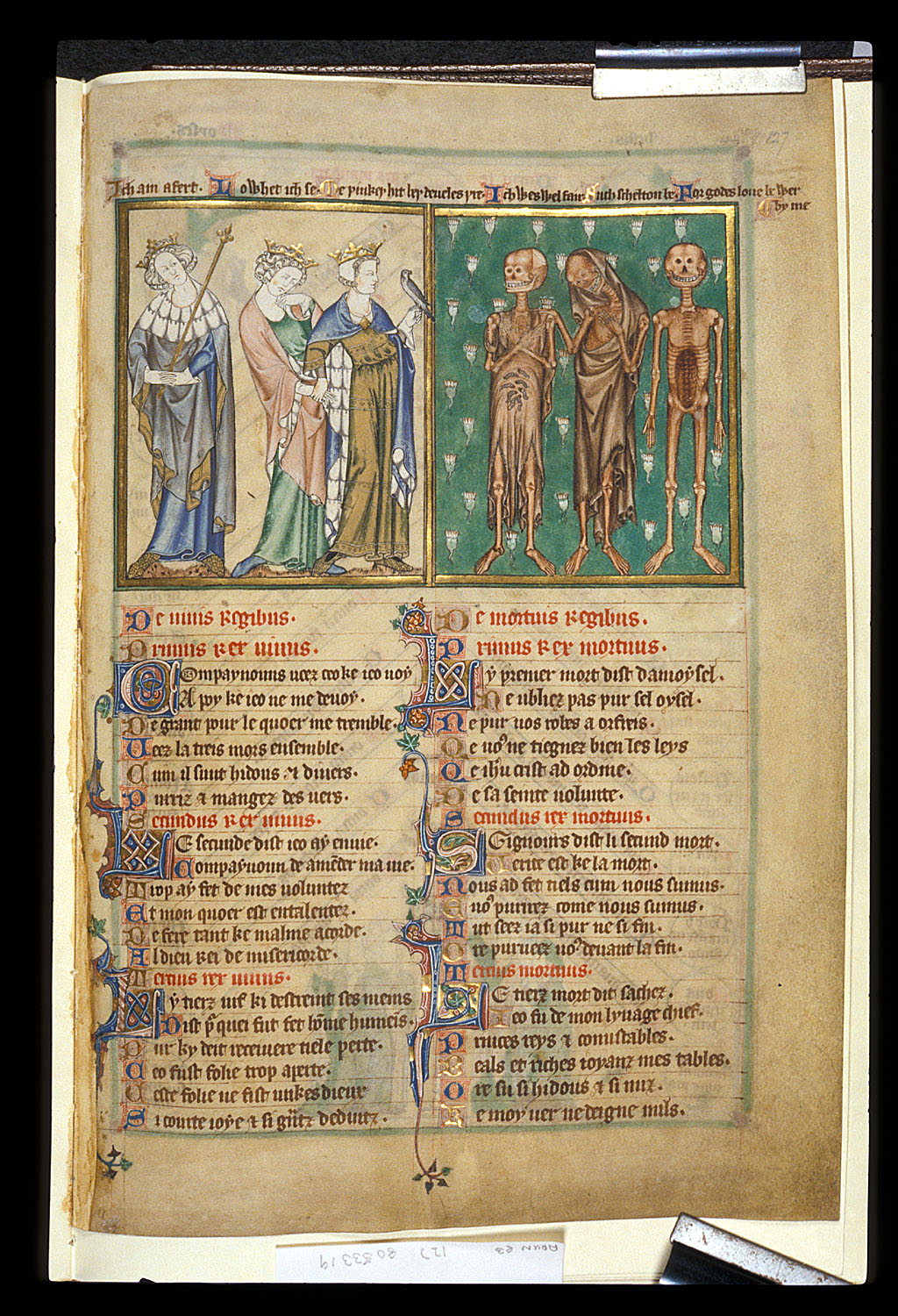

The skeletons reply “As you are now, we once were. As we are now, you will one day be.” This moral depiction, a reminder of mortality, was a popular theme throughout the 1300’s, and appears in church wall paintings and manuscripts.

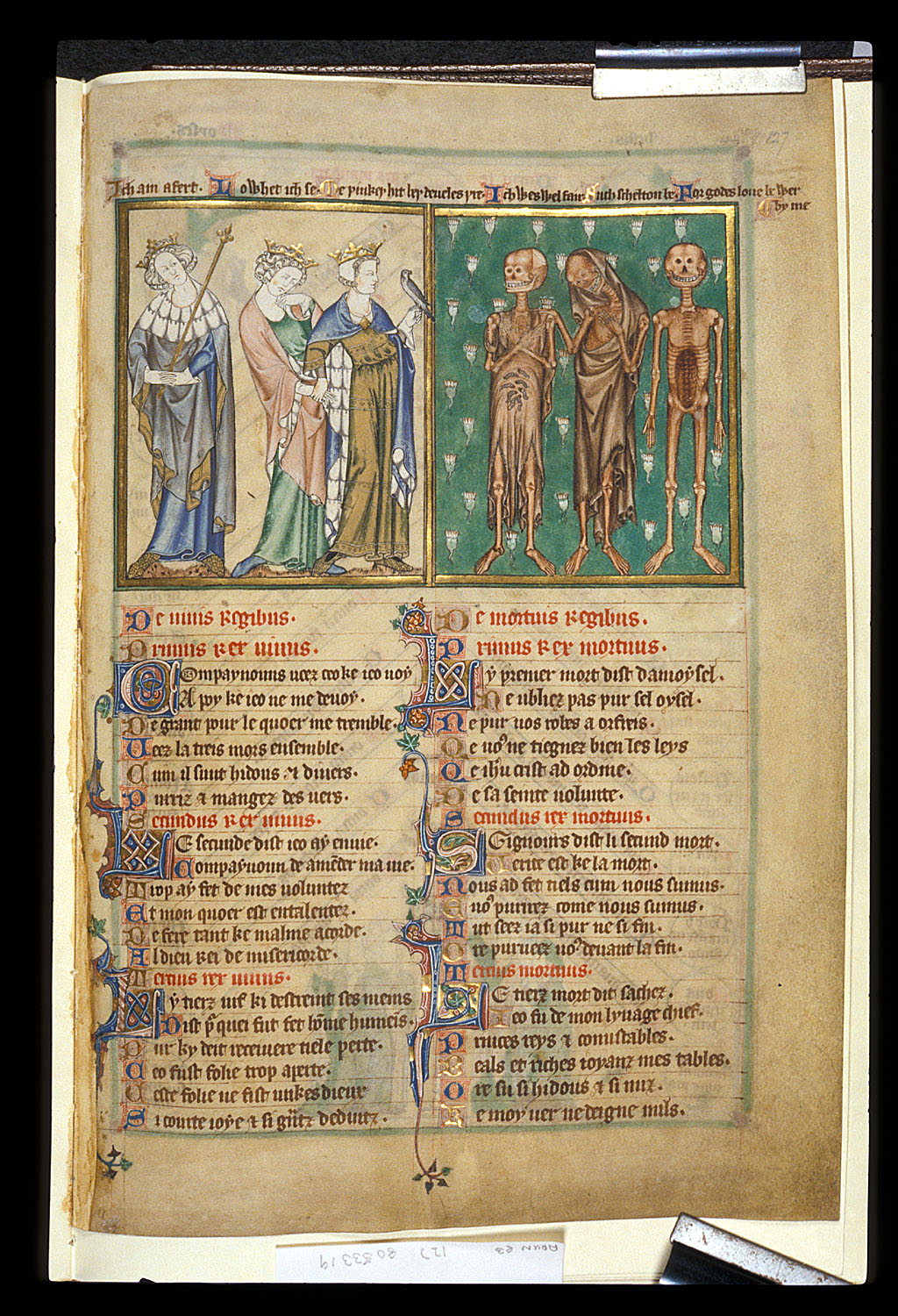

A picture from British Library archives shows a colour image:

Atribution: BL Arundel 83 f 127

On the tomb of the Black Prince, (died 1377), is inscribed in full the words of the popular French poem on this theme.

Such as thou art, sometime was I.

Such as I am, such shalt thou be.

I thought little on th’our of Death

So long as I enjoyed breath.

On earth I had great riches

Land, houses, great treasure, horses, money and gold.

But now a wretched captive am I,

Deep in the ground, lo here I lie.

My beauty great, is all quite gone,

My flesh is wasted to the bone

Very apt in view of the Prince’s pre-eminence as the eldest son of the great King Edward III, but who tragically pre-deceased his father.

The Wheel of the Five Senses is another moral, rather than religious theme:

The King, controlling the wheel, represents reason. Reason should control the passions, the five senses. Here we can see the spider’s web (touch), the wild boar (hearing), and the vulture (smell). It was thought that vultures detected their prey by smell, although now we know that they see their prey. The other two senses are – sight, depicted by the cockerel, the first to see the dawn, and taste, depicted by a monkey eating.

Numbers were important to the Medieval mind, and as well as the Three Living and the Three Dead, and the Five Senses, other paintings depict number sequences.

The Seven Ages of Man predates Shakespeare by over 200 years, but follows the same sequence as Shakespeare, showing a baby in a cradle, a child playing with a toy, following through the prime of manhood to maturity followed by decrepit old age.

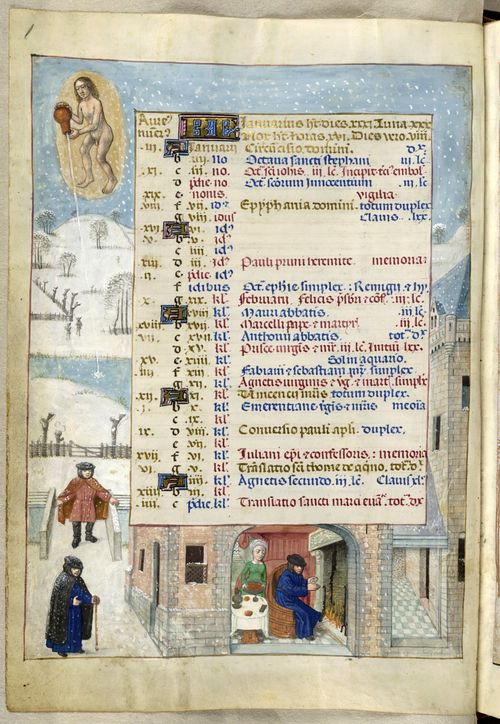

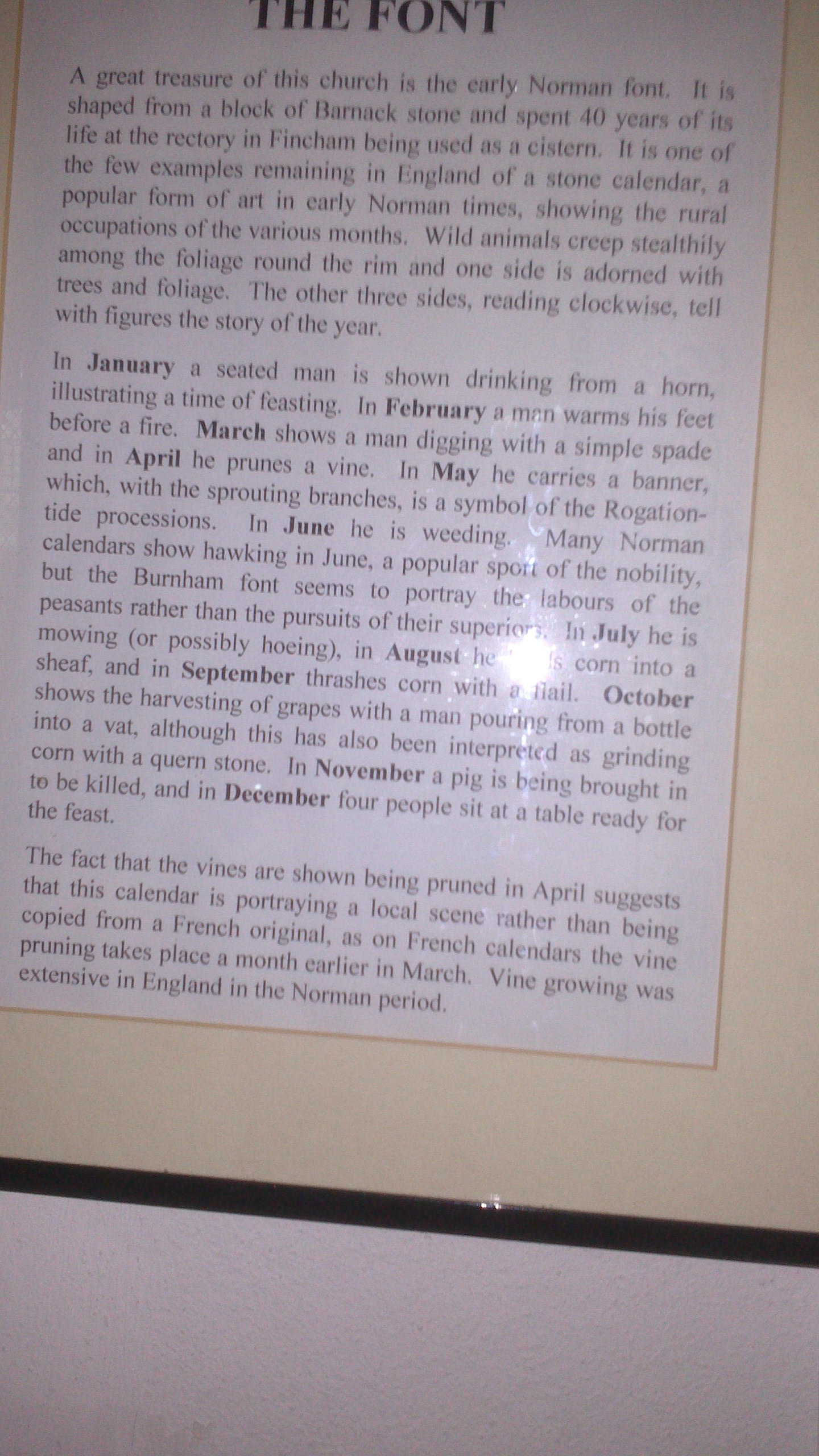

A sequence of the Twelve Labours of the Months starts with January, showing a peasant warming himself by the fire:

Most of the other months are too damaged to see, but December shows the ritual celebration of killing the pigs for Christmas:

Feasting would have taken place in this grand, decorated chamber, and there are paintings of musicians around the ceiling, indicative of private entertainment available to the wealthy. Here is a set of pan-pipes:

Other paintings, perhaps done by an apprentice, as they seem cruder, depict aspects of rural life:

Rabbits were an important source of food and fur for clothing, and the pollarding of trees ensured a constant renewal of supplies of wood for fires. Pollarding is still practiced in local woodland and wild-life areas to this day.

Rabbits were an important source of food and fur for clothing, and the pollarding of trees ensured a constant renewal of supplies of wood for fires. Pollarding is still practiced in local woodland and wild-life areas to this day.

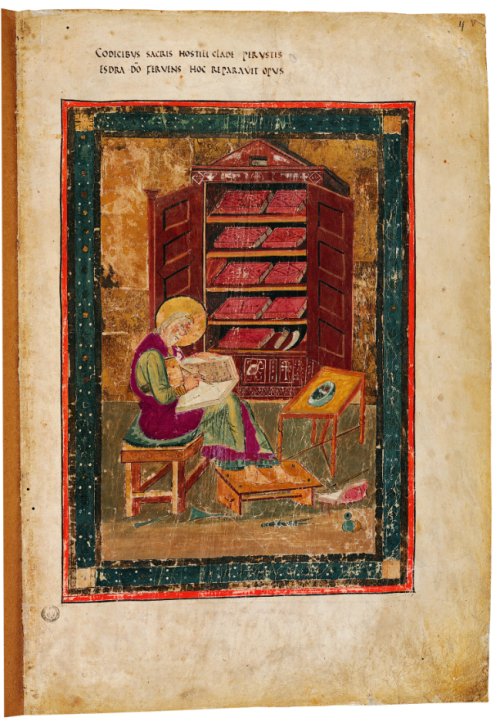

As education had been their means of advancement, themes of learning are also seen in the chamber:

Here a woman sits at a window and teaches a child. The seat by the narrow lancet window ensures maximum light bounces off the curved wall.

Here a woman sits at a window and teaches a child. The seat by the narrow lancet window ensures maximum light bounces off the curved wall.

The pictures are dated to approximately 1320- 1340. These dates have been worked out by reference to the style of the Kings’ crowns, and the style of clothing worn by this fashionable young man:

The closure of the period (1340) is calculated by a shield showing Edward III’s coat of arms before he announced himself also King of France. The Ducal Tower in Poland calculates that its date of construction and the dates of its paintings are almost identical with Longthorpe’s, indicating an international fashion trend in building and decorating.

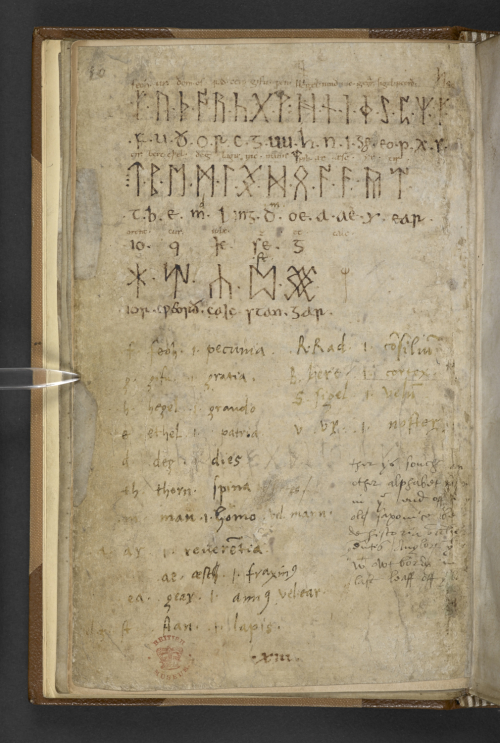

This British Library manuscript shows a King supervising the building of a Tower. The location is Northern France and the date early 1300’s.

Attribution: BL Royal 14E III f.85v

Summary

By a lucky chance, Longthorpe Tower has survived. It is situated in a quiet backwater in a small village outside a town which escaped, until recently, major re-development projects. The paintings survived because they were white-washed over rather than being “re-decorated” in the latest style. After the Fitzwilliam family acquired the Manor in the early 1500’s, The Tower was not their main residence, and it was used as a farm storage building, left undisturbed. The Tower was donated to the nation by the then owner, Earl Fitzwilliam, shortly after the paintings were re-discovered in 1945.

Today, volunteers show and explain the paintings to the public, and a growing body of background knowledge is being accumulated by experts in the field.

Rabbits were an important source of food and fur for clothing, and the pollarding of trees ensured a constant renewal of supplies of wood for fires. Pollarding is still practiced in local woodland and wild-life areas to this day.

Rabbits were an important source of food and fur for clothing, and the pollarding of trees ensured a constant renewal of supplies of wood for fires. Pollarding is still practiced in local woodland and wild-life areas to this day. Here a woman sits at a window and teaches a child. The seat by the narrow lancet window ensures maximum light bounces off the curved wall.

Here a woman sits at a window and teaches a child. The seat by the narrow lancet window ensures maximum light bounces off the curved wall.

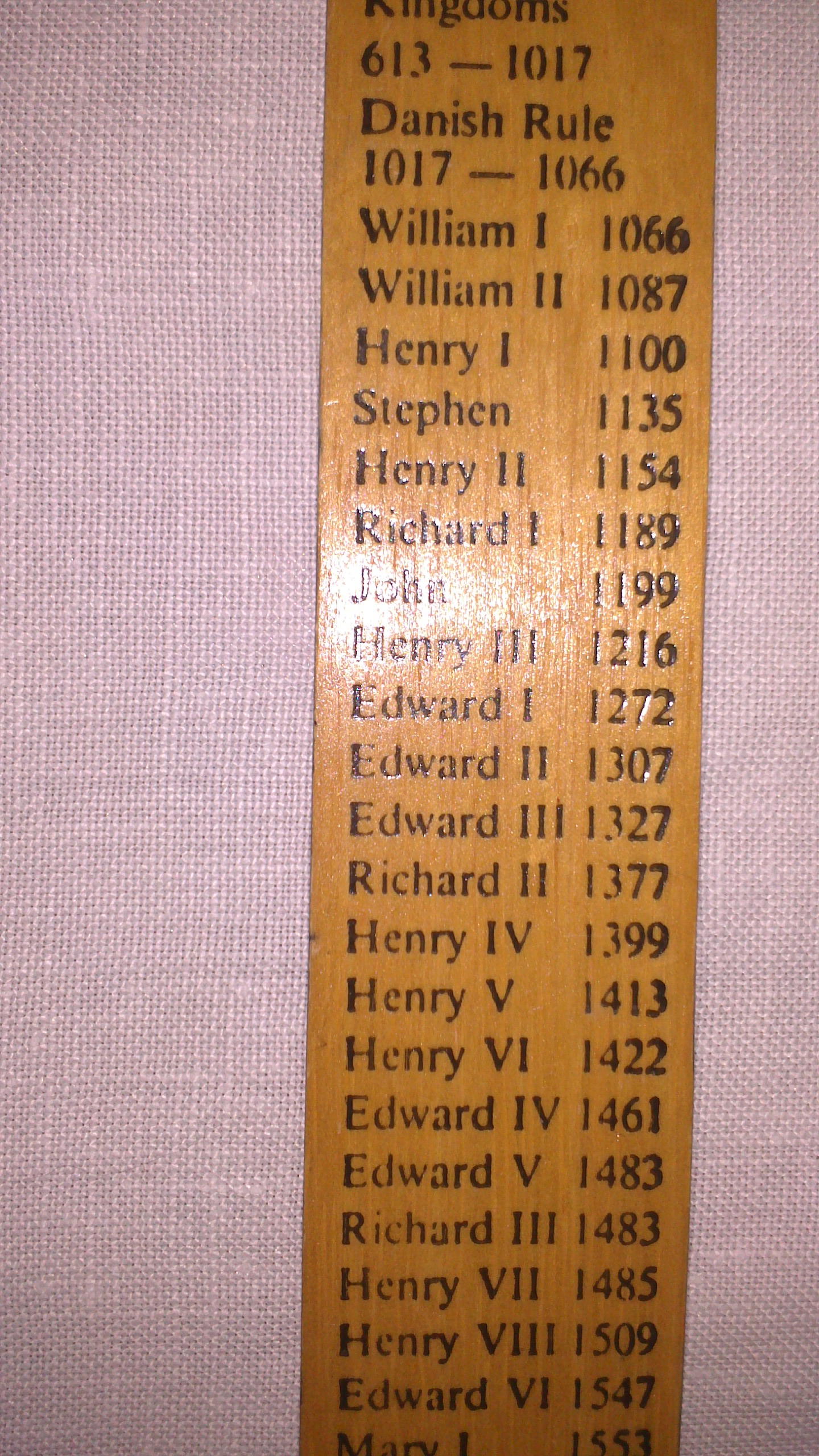

This is my History Ruler, which I have kept since my children were at Primary School, over a quarter of a century ago. Still in very good condition, not chewed, or splintered!

This is my History Ruler, which I have kept since my children were at Primary School, over a quarter of a century ago. Still in very good condition, not chewed, or splintered!